The UDHR in 2021 and Beyond: Its Implications in the Digital Age

On the 72nd Anniversary of the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, its foundational principles are just as relevant in the digital age and a useful reminder for the new U.S. administration.

By: Aamina Shaikh, Staff member

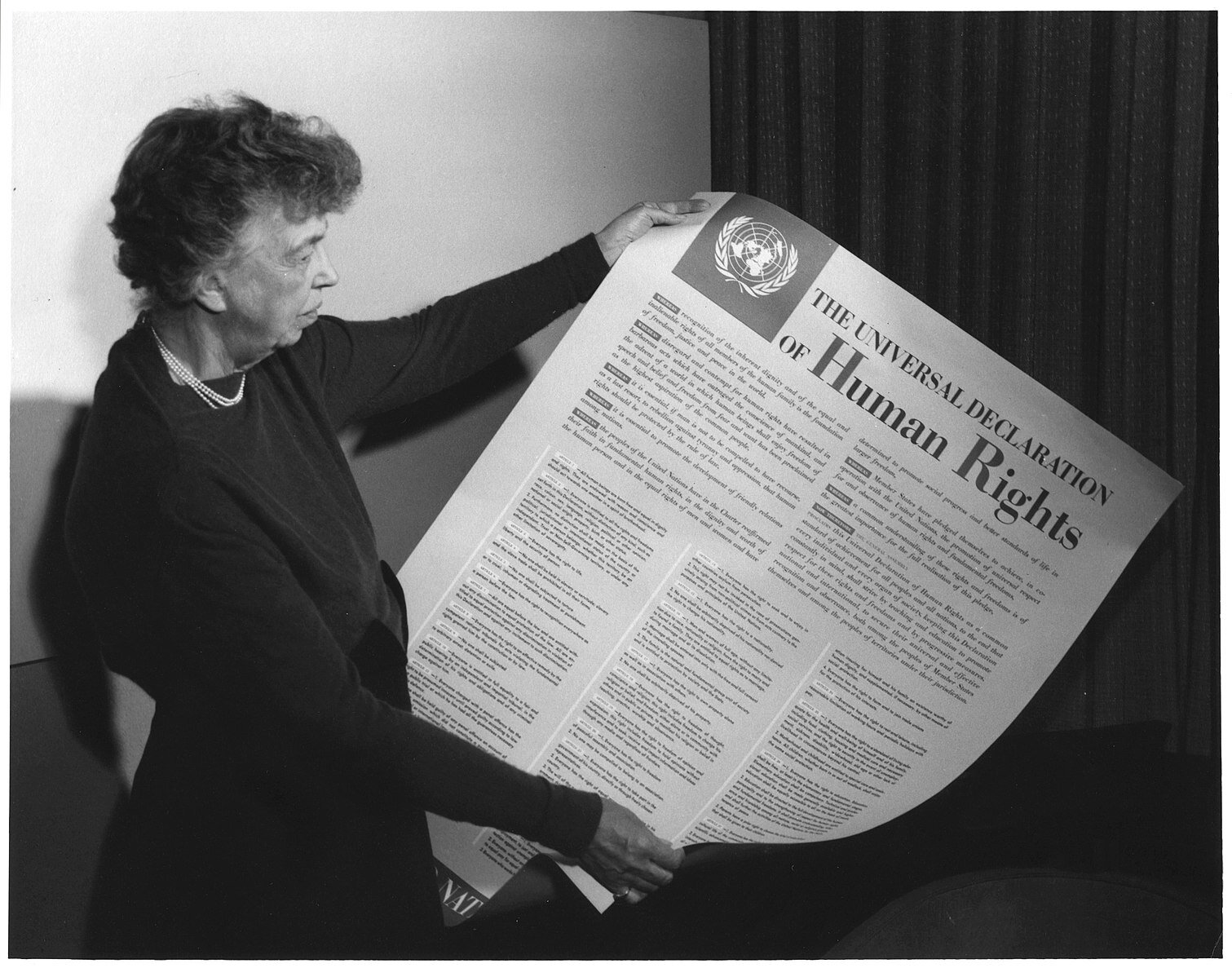

December 6th, 2020 marked the 72nd anniversary of the ratification of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). When it was drafted in 1948 — by a committee led by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt — it was a nonbinding document that, to a world reeling from fascism and still beholden to colonial powers, seemed naively aspirational. The text’s thirty articles detailed the unalienable “fundamental freedoms” of every human being, regardless of nationality, race, gender, or “any other status.” However, in the decades following, the UDHR has become a set of standards and principles for almost every facet of international law, and a foundation of international human rights law. It is a testament to the progress made toward equal rights and a reminder of the ideals we must still strive toward.

The challenges of the past year forced the global community to consider how we can continue to progress to the ideals enshrined in the UDHR. Though the world seventy-two years ago was no stranger to poverty, disease, and violence, the drafters could not have predicted how interconnected our responses to these threats would need to be. Furthermore, as the new administration has committed to a new approach in engaging with the international community, the UDHR can once again provide guidance for facing the global threats of the future. In particular, the articles of the UDHR can shape the Biden administration's approach to dealing with the challenges posed by artificial intelligence (AI) in the decades to come.

The urgent need for regulation of data gathering and use came to the forefront in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election. Employees of the political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica testified about their targeted use of Facebook user data, and Facebook, Google, and Twitter executives were repeatedly brought before Congress to answer for the role that artificial intelligence played in spreading misinformation on their platforms. The role of machine intelligence in perpetuating racial bias in the criminal justice system, surveilling ethnic minorities in China, and making us increasingly dependent on technology platforms during COVID-19 lockdowns are just the beginning of the challenges the governments will have to face when assessing how to effectively use and regulate AI.

President-elect Biden has stated that we should be “worr[ied] about the concentration of power [and] about the lack of [user] privacy” in the tech industry. There are also signals that his administration will take a stronger stance against big tech than the Obama administration: he is expected to continue antitrust litigation against Google and has also pledged to try to make online platforms more liable for content by revoking Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. While tech regulation may not be a focal point of the administration’s early agenda, determining the conceptual basis for regulation is necessary for coherent policy. The threat of public concern has caused large tech companies to promise to continue their foray into AI only within “ethical” parameters. The precise delineation of these ethical boundaries, the penalties for not violating them, and the societal input into what ethical norms should take precedence have largely been left unregulated or under-regulated. Amorphous ethical norms can allow for a flexibility that allows decision-makers to prioritize certain ethical values over others when faced with difficult choices. However, the UDHR, with its set of universal human rights that has become customary international law, is a more robust, credible, and accepted way of evaluating the need for regulation that will have impacts far beyond America’s borders.

There is, of course, no easy way to do this, but recognizing that AI advancement will likely be one of the defining characteristics of this era is a start. The advancement of AI must be addressed with the aim of long-term global stability, rather than short-term U.S.-centric profits and policies. Article II of the UDHR, the right to nondiscrimination, provides a fundamental guideline that should be applied here. It sets out the basis of the UDHR, stating that “[e]veryone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms... in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind,” including race, sex, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, other status, or the country to which a person belongs. This should be the starting point for a Biden administration tech policy aimed for 2021 and beyond.

One of the most dangerous developments in AI technology is its supposed ability to employ machine learning to not only identify people who may have committed unlawful acts, but to predict who may commit them in the future. As a ProPublica exposé made alarmingly clear, machine learning uses discriminatory inputs to estimate the likelihood of a person reoffending, affecting bail amounts and sentencing lengths, and disproportionately harming Black Americans. The for-profit companies that determined the algorithm did not overtly select race as a factor. However, because a non-racially discriminatory outcome was not prioritized or effectively regulated, factors that disproportionately affect lower-income and Black Americans, such as joblessness and social marginalization, were included without nuance. Nondiscrimination on the basis of race as both a guiding factor in the inputs and outputs of AI may seem elemental, but adhering to it as a corporate and regulatory foundational principle is quite evidently needed, as the UDHR reminds us.

Human rights - particularly the foundational ideals of the UDHR - should be incorporated not only into the way Congress structures new regulations, but into the ways that businesses pursue and implement new technologies. While regulation and public approval may be the limit of the tools that we can use to effectively monitor tech companies, the UDHR provides a basic set of legal obligations that have withstood the tests of time and are a useful reminder in the post-Trump era.

Aamina Shaikh is a second-year student at Columbia Law School and a Staff member of the Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. She graduated from the College of William and Mary in 2014.